Ahead of the Curves: Insecurity & Globalisation - The Return of Onshoring

This discussion took place in May 2022 as part of the Ahead of the Curves series, in partnership with Stifel Europe. This phase of the programme focuses on the links between insecurity & Globalisation and the return of onshoring.

You can also listen to the podcast interviews which provoked this discussion here.

Back in 1920 JM Keynes wrote about the last days of La Belle Epoque, a war-free period of unprecedented globalization that occurred in Europe from 1870 to 1914. “The inhabitant of London” Keynes wrote, “Could order by telephone, sipping his morning tea in bed, the various products of the whole earth.” This type of fortunate Londoner “regarded this state of affairs as normal, certain and permanent”. In 1914 foreign assets accounted for 20% of GDP but didn’t return to that level until 1970 and another age of normality, certainty and permanence in which a Londoner can now dial up an Uber Eats app meal of Peruvian mangoes, Italian pecorino, and Guatemalan asparagus, as well as his cup of morning tea.

Not long ago, the globalisation of our present age seemed a similarly inexorable force. We saw the fall of the Berlin Wall, a triumph of liberal democracy and shipping containers crisscrossing the world in their millions. But, as Aris Roussinos has written, “Like a pistol shot in 1914 Sarajevo, COVID can be seen as a chance event ushering in the end of a tottering old world and the beginning of a new one. A historical accelerant speeding along changes that were, perhaps, always inevitable.”

The week before the latest discussion in the Jericho series, in association with Stifel, Mcdonald's withdrew permanently from the Russian market - a symbol, if one was ever needed, of the high-water mark of late 20th and early 21st-century globalisation.

Eithne O’Leary, President of Stifel Europe, opened the debate. “It often feels as if we have grown accustomed to once-in-a-lifetime shocks coming every 12-18 months. The pandemic has altered our view of the world showing how vulnerable some systems are. More damaging to our view of the world order has been the Russian invasion of Ukraine – it’s been painful in quite unexpected ways. One more concerning angle is how the sanctions on Russia are splitting the world and how one manages these dilemmas if they become permanent. Maybe free markets cannot answer these questions in a very changed world order.”

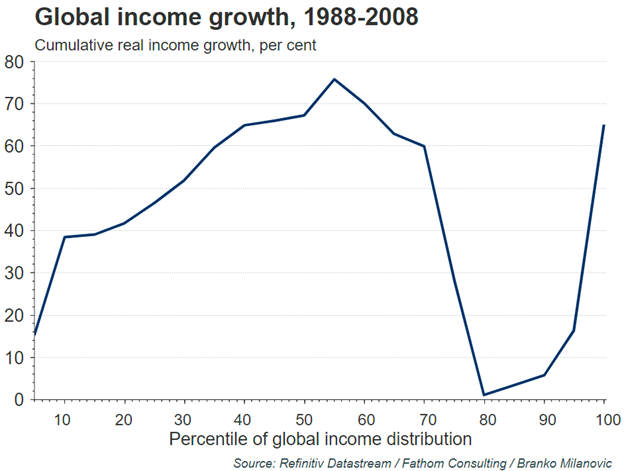

The economist Erik Britton showed a graphic by Branko Milanovic:

“This graphic,” he explained, “Tells the story of what has happened over the last few decades – it shows what's known as the elephant chart. You’re looking at growth in income at a global level. However, where it’s falling from 65% onwards is entry-level for the working population in advanced economies. But you can see it then picks up towards the 1% richest global population.

“This has arisen because of globalisation and the growth of income for people in China – people in the 30-40% income deciles globally. But this advance has come at the cost of people in the working population in advanced economies. And this failure to improve their standards of living is partly why populism and nativism arose.

“I don’t think you can say that globalisation is a bad thing for inequality globally. We should care about the poor in the developing world. We have seen a specialisation in what advanced economies are good at. But we can’t allow income growth like the downward fall of the elephant’s trunk and expect that people in Western democracies will settle for it and vote you back into office.”

Erik works in Washington and has a sense of a strong political mood there. “Back in the Cold War, there was concern about the US falling behind that resulted in the development of Operation Paperclip [The primary purpose for Operation Paperclip was U.S. economic and military advantage in the Soviet–American Cold War, and the Space Race.]

“Now they are doing Paperclip again but in terms of where the US is lagging behind China. Extreme concern about the open embrace of China is a thing of the past – everyone would reject this regardless of political stance because of populist reasons and national security considerations. But, of course, one has to ask to what extent is the private sector in the US a lever of economic statecraft?”

The group agreed that it’s a valid question whether the private enterprise had devoted itself sufficiently to food and energy security. But is that its job? Do nations now require an Industrial Strategy towards which business is actively steered or even cajoled to achieve this?

The economist Vicky Pryce pointed out the shortcomings of narrow-minded protectionist nationalism as a revolt against globalisation. “The problem is compounded by individual countries trying to focus on their own security and self-sufficiency while forgetting that going about it on one’s own won’t work. That is obvious already in the energy sector where the West working in a reasonably coordinated way in the current conflict with Russia, has much more of an impact and leads to far better results. Similarly, the attempts to be self-sufficient, or at least not as dependent on countries like China in other sectors, such as semiconductors, it doesn’t make sense and it won’t succeed, it will be a waste of resources to have each country try to be its own semi-conductors centre of excellence. Much more can be achieved if the effort to be a major producer of semiconductors to rival other centres is done as a joint European effort, tapping into distinctive countries’ competencies and also encouraging economies of scale. We see the EU certainly beginning to move in that direction and the UK needs to be plugged into that.

“But this requires coordination and also more guidance from governments, working side by side with industry. So, the question is whether markets will accept more government interference. They may have no choice. There is already considerable government involvement in the markets for food; oil and gas; renewables, pharmaceuticals etc. But as we are moving into a new era where the need for increasing self-sufficiency becomes paramount it requires re-thinking and re-organising production and supply chains but also aligning incentives and a lot more sharing with friendly neighbours. There will also, in this new geopolitical reality, need to be some rethinking of what type of investment is now acceptable for ESG funds. It looks like we will need to invest in oil and gas for longer than we thought and also in defence. That poses problems that will need to be resolved.”

Simon McDougall was asked whether the current direction of travel is a sign of the defeat of The Big Tech dream which promised it would democratise and bring down international barriers as it brought us all closer together.

“I think what Big Tech has done has on some levels reduced friction that was there before,” he said. “There were hindrances to global trade and it’s enabled globalisation and accelerated inequalities in doing so. The trend of data localisation preceded a lot of the factors we see right now. Data is being limited and onshored by national states due to a mix of human rights and trade concerns.

“The new wave of technology regulation going through Brussels is a recognition that GDPR was insufficient in and of itself. It may enable better protection for individuals and more data for non-US organisations. Maybe better late than never – we don’t know where the next stage of innovation will come from.”

Lesley Smith reminded everyone of the human factor. “The other thing that all tech companies get out of globalisation is global talent management. The pandemic showed people that they didn’t need to get tech visas. Business can get the best talent and keep them where they were. There is a question for industrial policy for all governments – in the UK for a bit it meant working with the tech industry with, tax breaks and the like. But governments need to think about what it is to have an industrial strategy. The French food production industry is regarded as strategic and they champion that. Today’s government needs to decide what it wants to champion and how that can be effective. Past governments really championed financial services with tax breaks on innovation and policies to make it easy to attract worldwide talent. That needs to be revisited in the post-Brexit, post-pandemic world.”

Sanjay Patnaik of Brookings in Washington said, “In the US there is pushback on efforts to control the private sector but there is recognition across the political spectrum of who we don’t want to be dependent on. The expectation that China would democratise more as it became more integrated into the global economy was clearly incorrect. In fact, the opposite has happened as it has cracked down more on dissent and become more autocratic. I think that we will see some pullback from governments and businesses from both China and Russia. We should try to disentangle ourselves as soon as possible because the costs will be much higher if you wait until the last moment. For instance, if China invades Taiwan there will be huge repercussions.”

Wendy Jephson of LetsThink acknowledged a major problem approaching: “We see these vulnerabilities, ESG concerns rising but currently it’s not a quick easy lift and shift. Change has to be done in a cost-effective way and our outsourcing of the requisite skills has left us with deficits in our innovation toolkits. Where there is a will there is a way though - people who are innovating will still want to tap into global markets and capital flows support the trends so provided the innovation is on-trend generating demand our investors have the capability to fund these skills gaps.”

Eithne O’Leary then pointed out that, “Erik’s chart reminds one of the central hypocrisy that we’re all in favour of democracy until people in our country vote differently to how we would like to see them vote. Brexit and Trump show this very clearly.”

Vicky Pryce also wondered about the democracy dividend: “The interesting - and worrying - aspect of globalisation is that the benefit it has brought to a number of emerging but also some developed nations, has not been met with much less populism. This may indeed be because those in the middle-income brackets, as shown on Lanker and Milanovic’s elephant curve, haven’t benefited as much from the growth that globalisation has brought with it.”

Madison Kominski who is American but educated partly in London was asked whether the UK remains an attractive place for migrants despite increased populism. “Even though there is an evolution happening we still have a way to go before anyone feels that the UK is no longer a place that they want to be. From my Masters, most students were not from the UK but felt that studying here would give them more opportunities than staying at home and a lot of that comes from the feeling that, while other countries are progressing and developing and taking away market share from the UK in certain sectors, it’s still not at a point where they can progress in their career in the same way.”

Lama Zaher from Lebanon lives in a country rocked by instability for decades. It’s hard to find much globalisation dividend there “We have inflation at 200% so the economy is in trouble and has been since 2015 despite efforts to advance the tech sector. In Lebanon we never had an industrial strategy, we imported everything and never exported anything – the central bank realising the economy is collapsing tried to capitalise on assets the country has, mainly its human capital and hence attempted at growing the tech sector and the knowledge economy. While the sector had a lot of potential, the expectation for a rapid return on investment was unrealistic and unstrategic.”

As the Shadow Minister for Digital, Science & Technology, Chi has to consider these issues on a daily basis: “Many would argue that globalisation has not delivered for working people” she said. “Working incomes in the UK have not increased at all in the last 10 years and the shift to populism has been driven by a sense that governments are not working for the people. Tory Industrial strategies have come and gone and we’ve had Challenges, Policies and Sector Deals but we haven’t had any long-term view of what kind of economy we want to achieve. That’s why were in a situation of low growth, high inflation, low wages and high tax.

For example, my party has said that we should increase R&D spend, leveraging the private sector in terms of investment. I don’t feel Biden’s worker-centric trade policy is just another word for protectionism but globalism can just be a race to the bottom. The trade deals should work in people's interests. People confuse picking winners with picking particular companies vs sectors – I’m not sure saying quantum computing for example is an area the UK needs to be strong in is picking a winner? DeepMind is an example of where a Labour government would have acted differently. Maybe it would have been an idea to have strengths in 5G and not spend billions taking Huawei out of our network by picking a sector winner earlier. Governments need to look forward at least 5 years.”

Meanwhile, food and energy security are becoming and subverting Net-Zero. And several contributors pointed out that food price inflation is the world’s number one predictor of conflict. Sanjay reminded the group that, “we will see a huge impact as people cannot afford as much food as before. India is stuck in the middle between the West and Russia and China. They will try to thread the needle to move closer to a western alliance but they won’t be openly going against Russia anytime soon I think.”

Erik agreed: “The evidence over the cold war period was that the countries who succeeded in terms of threading the needle did best in terms of growth so there is a strong incentive for all emerging economies to do that. Part of the redistribution to the extremely wealthy is away from those who work for a living to those who own things for a living. They have been able to extract labour for a cheaper and cheaper price.”

Many of the richest tech. companies in the world are all from the US and have doubled their wealth since the beginning of the pandemic. Whether this is distinguishable from globalisation is interesting. But combined with the cost-of-living crisis this is jarring. We are reaching a point where the world economy slows the inequality issues will be a driver everywhere.

And the Super Rich in China are clearly on a warning as the politburo tightens its grip. Noam Scheiber has written in The New York Times: “China is effectively forcing other countries to adopt some of its own industrial policies because a free market in which only one side plays by the rules isn’t so much a market as a sucker’s game… after decades of free-market orthodoxy in which protectionism became taboo among both parties’ elites, it is the rise of China, above all else, that is bringing nationalistic management of the economy back into the political mainstream.”

However, the Chinese garment industry will not be pleased that the latest series of Love Island is promoting the end of fast fashion. It features clothes bought on Depop and eBay. Onshoring and the new frugality has a very 1914 feel to it.

The discussion was attended by:

Erik Britton, Managing Director, Fathom Financial Consulting

Matthew Gwyther, Partner, Jericho Chambers

Wendy Jephson, CEO & Co-Founder of LetsThink, Former Head of Research & Ideation - Market Technology, Nasdaq

Madison Kominski, Investment Banking Analyst, Stifel

Simon McDougall, Chief Compliance Officer, ZoomInfo

Eithne O’Leary, President, Stifel Europe

Chi Onwurah, Labour MP for Newcastle upon Tyne Central, Shadow Minister Digital, Science & Technology

Sanjay Patnaik, Director Center on Regulation and Markets, Brookings Institution

Vicky Pryce, Economist and Business Consultant, Board Member Cebr

Lesley Smith, Corporate Advisor

Lama Zaher, Managing Partner, Beyond Innovation and Technology – Lebanon